The Good Boss (El buen patron) – Film Review

Reviewed by Damien Straker on the 18th of April 2022

Nixco and Sharmill Films present a film by Fernando León de Aranoa

Written by Fernando León de Aranoa

Produced by Fernando León de Aranoa, Jaume Roures, and Javier Méndez

Starring Javier Bardem, Manolo Solo, Almudena Amor, Óscar de la Fuente, Sonia Almarcha, Fernando Albizu, Tarik Rmili, Rafa Castejón, and Celso Bugallo

Cinematography Pau Esteve Birba

Edited by Vanessa Marimbert

Music by Zeltia Montes

Rating: M

Running Time: 120 minutes

Release Date: the 14th of April 2022

At this year’s Academy Awards Javier Bardem should have been nominated for The Good Boss (El buen patron). Instead, he was a Best Actor nominee for the uneven biopic Being the Ricardos (2021). He played Desi Arnaz, the husband and business partner of Lucille Ball. The Good Boss is the better film. It features Bardem’s best performance since he won an Oscar for playing the villain Anton Chigurh in No Country For Old Men (2007). He proves he is infinitely more comfortable when performing in Spanish. It also helps The Good Boss is a busy but well-written satire about the social imbalance of Spain’s working life.

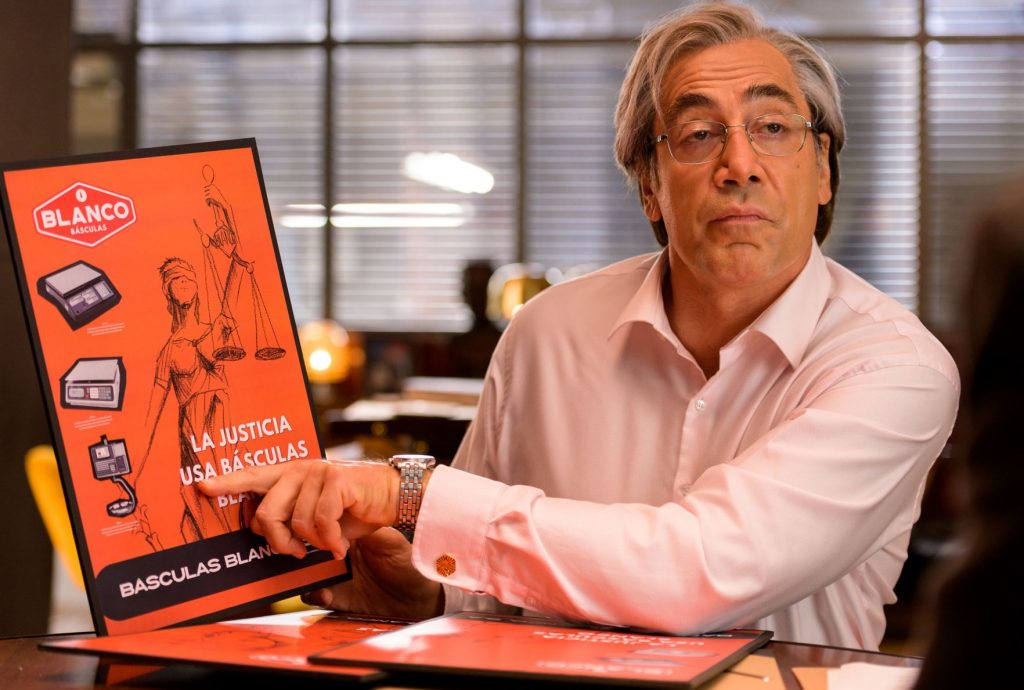

Bardem’s titular character, Blanco, is a businessman and showman. His factory, Básculas Blanco, manufactures scales. Within weeks, the company expects to receive a Business Excellence award. However, before it is finalised, there are several fires to extinguish. After all, Blanco declares, ‘if they hurt my company, they are my problems’. He is troubled by the dysfunctional behaviour of a key worker, Miralles (Manolo Solo). He continually makes mistakes with orders and fights with workers like Khaled (Tarik Rmili) on the factory floor. Blanco cannot fire Miralles though because he is one of his childhood friends. Meanwhile, Fortuna (Celso Bugallo), an elderly labourer, begs Blanco to help mentor his troubled son, Salva (Martín Páez). Blanco puts him to work in the clothing store of his wife, Adela (Sonia Almarcha). Blanco’s toughest challenge is an ex-worker’s dissent. Jose (Óscar de la Fuente) has been made redundant but is aggrieved by his meagre severance package. He protests outside the factory by pitching a tent and screaming into a megaphone. Blanco asks his security guard, Román (Fernando Albizu), to remove him but it is futile because he is on public property. Blanco distracts himself in the worst way possible. He is dazzled by the presence of Liliana (Almudena Amor), a beautiful intern who has started working for the company.

A positive trait of filmmaker Fernando León de Aranoa’s work is his consistently strong tonal control. Despite a plethora of interlocking subplots, Aranoa ensures each one is grounded. The dramatic heft he brings to proceedings amplifies the drama’s verisimilitude and the bleak climax’s power. A reference to The Godfather (1972) is befitting of the ruthless humanity projected throughout the director’s screenplay. Fortunately, the balance of power and working‑class conflict is matched by deft comedy, specifically the clever premise. Rather than adopting the safe perspective of repressed workers counterpunching their leaders, humour stems from Blanco’s disingenuousness. With charm and cloying earnestness, he refers to the workers as his family and stresses loyalty’s importance. The scenario is increasingly funny as Blanco’s dishonesty come to the fore and his power wanes. Blanco’s downward spiral follows a strict rule of comedy: punching up not down and taking aim at people in positions of power. It also helps proceedings that the humour resists verging entirely into parody. While deemed a ‘workplace comedy’, the comedy is not as broad as some major American sitcoms, such as The Office. The distinction is pivotal when balancing realism with traces of dark humour.

The visual stylisations remain as understated as the film’s wit. Boss is not a beautiful film, but consistent visual choices enhance proceedings. Glass panes are one such stylistic device. For example, Blanco’s office is surrounded by glass panels overlooking the factory floor. Meanwhile, Aranoa’s camera peers through the windscreen of Blanco’s car as he witnesses Jose loudly protesting. The glass surfaces are paired with the desaturated colour tones of the factory and Blanco’s grey hair and suit. The glass surfaces and muted colour grading subtly dramatise Blanco’s lack of empathy. He has no regard for his workers, his wife, or anyone. The only meaningful point in his life is filling the last open spot on his wall with the Business Excellence award. Aranoa resorts to a wide angle shot to frame the accolades Blanco has already received. The vision stresses the pointlessness of selling his soul for yet another prize. This is an example of how the visuals illustrate the psychology of the protagonist.

Bardem’s layered performance reinforces the actor’s dramatic range. He pinpoints Blanco’s oiliness, particularly when he says the female interns are, ‘like my daughters’ and describes Blanco as ‘one big family’. Yet he also relishes painting Blanco’s angst as his façade cracks. A chilling moment sees him scrub his hands so hard he almost bursts a vein. It recalls Macbeth’s hand washing scene, such is the final quarter’s Shakespearean tone. This is not to say the role is pitch black. Blanco humorously lack self-awareness. At a dinner party, he and his friend raise a toast to their humility and hard work only for Blanco’s wife to remind them they inherited their factories. The supporting performances impress too. Manolo Solo captures Miralles’ pitiful desperation to hold his marriage together while not being the victim he says he is. Similarly, Almudena Amor uses the quietest of looks to stress how Liliana is craftier than anticipated. In a small but impacting role, Moroccan actor Tarik Rmili makes a powerful statement about inequality. Khaled rejects Blanco’s line about family and points to his own dark skin. Another interesting role is the security guard who is friends with Blanco but sympathetic to Jose. True to all the characters, he is sharper than he appears upon the surface. Evidently, the impressive cast relishes the solid writing and the characters’ multidimensions.

The conflict between Blanco and his workers memorably depicts the façade of modern capitalism and industry. Leaders posture as being good natured while undermining the working class through ego, dishonesty, and self-importance. This is not a new thematic angle. However, it is reinvigorated by transcending simplistic working-class heroism and the broad American workplace sitcom. Instead, adopting the boss’ perspective is a crafty avenue for showing how everyone possesses different sides to their personality. Each character is attempting to shift the balance of power. Aranoa underlines this through references to Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle and Blanco’s obsession with realigning a set of scales. Meanwhile, Bardem’s exploration of Blanco’s moral decline proves with excellent material he can exceed one‑dimensional typecasting. Tracing the different facets of this humorous but repellent fellow is a task he excels at with aplomb. Blanco himself would have relished the Oscar buzz.

Summary: The Good Boss memorably depicts the façade of modern capitalism and industry. It is also the film for which Bardem should have been nominated for Best Actor.