Professor Carole Cusak Interview (Britannia Series 1)

With Britannia Series 1 now available on Blu-ray and DVD, we interview Professor Carole Cusak, an expert in Religious Studies, European Mythology and Contemporary Religious Trends who gives the facts about this amazing time period.

What drew you to Religious Studies and English Literature?

I love reading and in high school had a passion for history and archaeology. Yet, at university my interests shifted to mythology (a form of literature, after all) and religion (especially ancient and medieval religion, both Pagan and Christian). I wrote an Honours thesis on 19th century interpretations of Viking Age myth and religion, then a PhD on the conversion of the early medieval Visigoths, Anglo-Saxons, Franks, and Scandinavians to Christianity.

As a medievalist, what’s the strangest fact about this era?

A weird tale is that of the green children of Woolpit, reported in William of Newburgh’s Historia rerum Anglicarum (1196) and Ralph of Coggeshall’s Chronicon Anglicanum (1224). Apparently, a strangely dressed green brother and sister appeared in Suffolk at harvest time one year in the reign of King Stephen (1135-1154). In a nearby town, Woolpit, people came to see the green children, who ate only beans for months while slowly becoming civilized. Their skin changed colour, and they learned to speak English and eat bread. The boy died, but the girl reached adulthood and married. Here’s a site that explains what their origin probably was: http://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/The-Green-Children-of-Woolpit/

Funniest fact?

Pope Stephen VI was pope in 896-897 AD. He hated his predecessor Pope Formosus and dug up his corpse to put him on trial in what is called the Cadaver Synod. The corpse was dressed in papal robes and was defended by a deacon (but as the corpse could not speak the deacon remained silent, too). At the end of the trial Formosus was found guilty (obviously), three fingers of his right hand were cut off, and his corpse was stripped, paraded through the streets of Rome, and thrown into the Tiber where currents tore it to pieces. OK, perhaps it’s not funny ha ha, but it does inspire (possibly nervous) laughter in me.

What do you think people of the 25th century will think of us in the early 21st century?

This question assumes that there will still be human society on Earth in the 25th century. I’m not entirely sure we should express such confidence. It also depends on what kind of future we have; will there be ecological awareness and a diminishing of population numbers, or the full Mad Max disaster (as an Australian, I love the original Mad Max trilogy). Either way, our values and assumptions are likely to seem as odd as those of the citizens of the 17th century seem to us. So, what’s odd about the 17th century? Well, perhaps not much. The majority of people were desperately poor, and religious mania was rampant. One of my favourite plays is Howard Barker’s “Victory,” which is about the Restoration. I saw it with my partner in 2004 in Sydney: https://www.smh.com.au/articles/2004/04/21/1082530225623.html. It offers a grim picture of life after the English Civil War

Tell us a little about “Britannia” Season 1?

“Britannia” calls to mind both “Game of Thrones” and (more powerfully, I think) “Vikings”. It is an imaginative rendition of a little-known era. It also has power in an era dominated by Brexit. Is Rome Europe? Is Britannia better off without Rome? We know that Rome wins and. Dominates Britain until 406 AD when the legions leave, because the core territory of Rome is under threat from the Goths (Alaric the Visigoth sacks Rome in 410 AD). The first series introduces Aulus Plautius, the general who leads the successful invasion of Britain, and the two British queens, Kerra of the Cantii and Antedia of the Regnii, who are locked in a conflict that pre-dates the Roman invasion. The Druids are important, as Veran (leader of what looks in twenty-first century terms to be a drug-fuelled cult) is a major character, and Divis, the renegade Druid, acts as guardian and guide to unlikely heroine Cait. There are beautiful landscapes and imaginative reconstructions of British Celtic townships, and there is violence, sex, passion and power. I think it is a series that repays viewing, taking its audience into hallucinogenic realms that challenge mainstream ideas about history.

Why do you think this era makes for good television?

The reason that the British Celtic era makes for good television is that it’s not well known or well-documented. People are better acquainted with the late antique “Arthurian” era (the fifth century AD, after the Roman legions departed England, and during the period when the Anglo-Saxons were invading and settling southern England). This is a chance to explore a mysterious part of the British past, before civilisation (in the form of the Romans, with their planned cities, straight roads, massive defensive structures like Hadrian’s Wall, elegant villas in the country etc) arrived. Life is closer to nature, and the inward-looking quality of British Celtic culture means that the Cantii and the Regnii have no idea of how the presence of Rome will change their land – and themselves – forever.

Do you think fans of “Game of Thrones” will gravitate to “Britannia”?

This is a definite possibility. However, there are important differences. “Game of Thrones” had an appeal to those who had already read George R. R. Martin’s novels, as well as those who were beguiled by the high-epic, fantasy plotlines. “Britannia” has a dramatic plot and there are mystical experiences aplenty (mostly hallucinogenic and provoked by drugs) but importantly it’s not fantasy, it’s not imaginary, but an unexplored aspect of history (even though “history” is used pretty loosely).

In your professional opinion, why do you think the culture of the Druids has a mystery surrounding them?

The Druids were religious professionals who were connected in the Greek and Roman texts with other ancient groups. So in the first century AD Dio Chrysostom equated the Druids with the Magi of Persia, the Brahmins of India, and the Egyptian priests. They were a learned class in an illiterate society, in which religion was the most important force. But we don’t know that much about them, which creates mystery.

Given the timeframe of Britannia, what was the Romans biggest victory?

There’s only one text that tells us what Aulus Plautius did in 43 AD, it’s Cassius Dio’s History of Rome (Book LX, Chapter XIX). A few other texts mention him in passing (Tacitus’ Agricola and Suetonius’ biography of Vespasian). The series doesn’t mention that Emperor Claudius came over with Aulus; after Colchester was captured and made the capital of the new province of Britannia he went home (he was in Britain for 16 days). The Roman conquest was relatively easy as the British tribes weren’t unified and were picked off one at a time. Legionary forts were planted to keep the peace, and roads and frontiers established to make monitoring and stabilising easy. Aulus Plautius made ‘client’ treaties with Prasutagus of the Iceni (Boudicca’s husband), Adminius of the Cantii, Cogidubnes of the Regnii, and Cartimandua of the Brigantes. That’s two of the tribes in the series …

Biggest mistake?

He didn’t really make mistakes. After a successful term as commanding officer, he was succeeded by Ostorius Scapula. In Rome Emperor Claudius honoured him with an ovation (equivalent of a modern ticker-tape parade, less distinguished than a triumph). Claudius and Aulus Plautius were friends and also related, as Claudius’ first wife was Plautia Urgulanilla, a kinswoman of Aulus.

Lastly, tell us a religious fact from this era that is uncommon knowledge?

Almost everything that people “know” about Druids is hotly contested. The Issue of human sacrifice was usually strenuously rejected by pro-Celtic people, who argued that the Greek and Roman texts that spoke of these practices were biased, untrue, propaganda that justified the Roman conquest. But there is archaeological evidence from all over Europe (and especially Ireland and Denmark) of bodies in bogs and tombs that were violently slaughtered in ritual ways. There’s two bodies found in Ireland, Old Croghan Man and Clonycavan Man, both of whom were killed hideously. Old Croghan Man had holes cut in his upper arms so he could be immobilised by a rope pulled through them, was. stabbed repeatedly and he had his nipples sliced, and was finally cut in half. Clonycavan Man was disembowelled, stuck thrice on the head with an axe and also had his nipples cut. The nipples were cut off to dethrone a king; in Irish texts to suck the nipples of a king was a sign of subjugation, of giving loyalty.

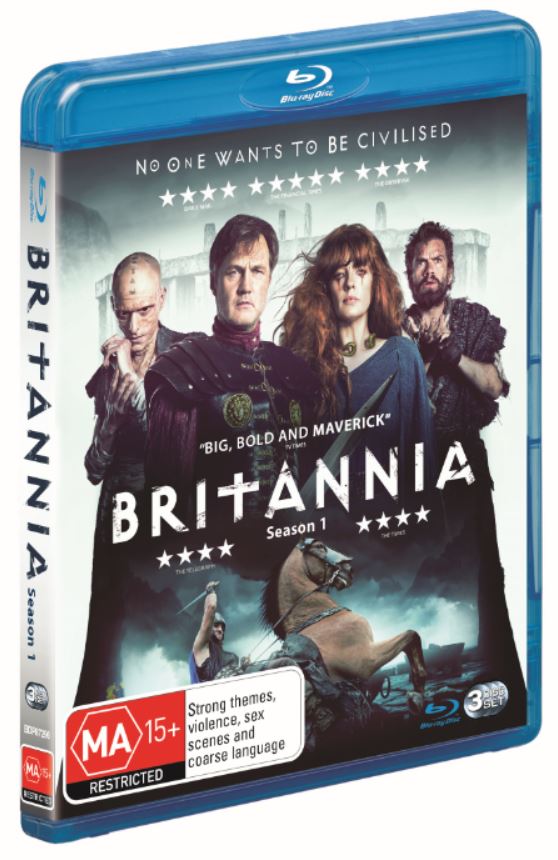

BRITANNIA SERIES 1 IS NOW AVAILABLE ON OUT NOW ON BLU-RAY AND DVD

For The Gods. For The People. For The Empire.

Britannia begins in 43AD as the Roman Army, determined and terrified in equal measure, returns to crush the Celtic heart of Britannia –a mysterious land ruled by wild warrior women and powerful druids who can channel the mysterious forces of the Underworld. Arch Celtic rivals Kerra (Kelly Reilly) and Antedia (Zoë Wanamaker) must face the Roman invasion led by the towering figure of Aulus Plautius (David Morrissey) as it cuts a swathe through the Celtic Resistance.