One Fine Morning (Un beau matin) – Film Review

Reviewed by Damien Straker on the 2nd of June 2023

Palace Films presents a film by Mia Hansen-Løve

Written by Mia Hansen-Løve

Produced by Philippe Martin and David Thion

Starring Léa Seydoux, Pascal Greggory, Melvil Poupaud, Nicole Garcia, Fejria Deliba, Camille Leban Martins, Sarah Le Picard, and Pierre Meunier

Cinematography Denis Lenoir

Edited by Marion Monnier

Rating: MA15+

Running Time: 113 minutes

Release Date: on the 8th of June 2023

The understated family drama depicted throughout One Fine Morning is effectively staged and moving to watch. The subdued filmic style that frames the story is courtesy of rising French filmmaker Mia Hansen-Løve. She was previously a film critic for the publication Cahiers du Cinéma. At forty-two, her work behind the camera has seen her emerge as a highly accomplished filmmaker. Her oeuvre, which includes the English-language drama Bergman Island (2022), has received critical acclaim. Morning further demonstrates her capacity to craft an understated adult-centric narrative. The director also imbues important socio-political conversations around age and draws a powerful performance from actress Léa Seydoux (Blue is the Warmest Colour; No Time to Die). The timeliness of the film’s themes and the emotion of Seydoux’s role prove instrumental in telling a story inspired by Hansen-Løve’s own ageing father before he passed away. The personal elements have clearly inspired her to tell the narrative in an uncompromising manner that firmly suggests a mature and talented filmmaker.

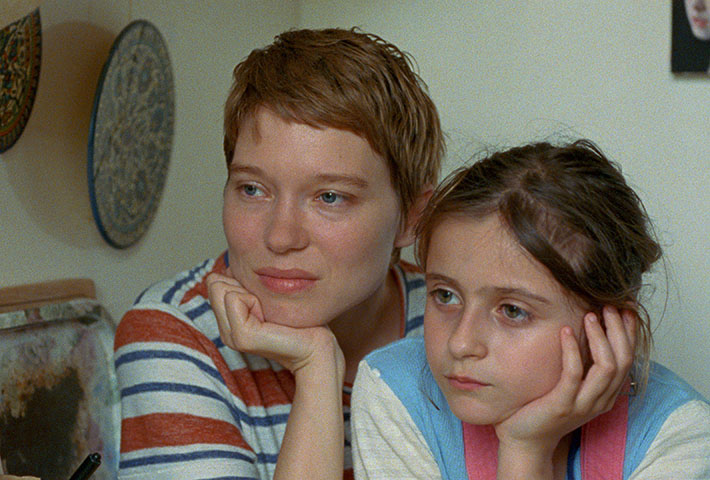

The juxtaposition of the film’s two plotlines calls for a highly sympathetic protagonist. The story introduces a hardworking single mother named Sandra (Seydoux). This highly intelligent, unwavering woman juggles various responsibilities in her Parisian life. She is a skilled language translator who we first see aiding American World War II veterans during a commemoration ceremony. Sandra is also devoted to her daughter, Linn (Camille Leban Martins). For the most part they share a loving relationship. Her greatest challenge is being a responsible daughter herself when caring for her ageing father, Georg (Pascal Greggory). Once a philosopher, Georg’s eyesight is failing so rapidly he needs help opening his front door. As the film progresses, a neurological disease renders his speech patterns increasingly incoherent and difficult to decipher. He longs for his companion, Leila (Fejria Deliba), who is rarely available to assist him. The difficulty of finding appropriate, affordable care in Paris is mostly in Sandra’s hands albeit with some help from her family, including Georg’s ex-wife, Françoise (Nicole Garcia), who is a political activist. Georg moves between four different age care homes because some of the facilities are expensive or unsuitable. To ease the stress in her life, Sandra begins an affair with a friend of hers, Clément (Melvil Poupaud). He is a cosmo-chemist who is married and has a young son. However, the love he shares with Sandra is potent and enriches their lives.

Hansen-Løve’s tight screenplay is elevated by its thematic goals of age and how brutal responsibilities influence our desires. Sandra works tirelessly in her job to help translate different languages. Early on, the veterans foreshadow the significance of the elderly in the story. Sandra is also challenged by the difficulty of choosing an appropriate age care home for her father and finding space for his possessions, including his extensive book collection. Some of the age care homes are completely inappropriate, such as one where the rooftop space is freezing cold and another where the elderly patients wander freely without close supervision from their nurses. The stress of age care and being a good mother is why Sandra’s affair with Clement is depicted without an overly critical lens. The chosen perspective is gentler than expected. Yet we realise Sandra needs respite and hope in her own life. One could argue Morning’s depiction of this affair is too soft. However, narrowing the romance to Sandra’s viewpoint creates empathy and dissolves potential cliches about her relationship unravelling. Instead, the director gradually progresses both storylines by complicating them with questions around whether Sandra will continue helping her father and if Clement will leave his wife. The contrast in the dramatic scenarios shows how tirelessly Sandra works to put others before herself while underlining the difficulty of having someone who meet her needs.

Morning is directed with a strong emphasis on social realism over aggressive melodrama and forced emotions. Hansen-Løve’s clear, natural visual style results from photographing scenes in 35mm film. This stylistic choice achieves high verisimilitude when staging scenes in the streets of Paris, age care homes, and French apartments. The residents in the age care scenes are also particularly well chosen and provide an often sombre but involving mood. Meanwhile, Hansen-Løve’s unfussed visuals resist overly formal choices, which influences her dramatic response to the themes. Many contemporary films falsely attempt to marry the difficult subject of age with glib commentary around immortality. The message is repetitive and hollow: no one is ever too old to see out their dreams. While not as brutal as Michael Haneke’s Amour (2012), Morning’s decisive realism, which stems from its tactile shooting style, applies sensitivity to its subject. The muted way Georg’s deterioration is shown frees the treatment from sentimentality. Similarly, Sandra’s relationship forgoes twohanded arguments to depict the natural, unexploited physicality of the story’s unlikely couple. Even the film’s political discourse, including criticism of how Emmanuel Macron’s government has failed age care, is blunt but not overstated. Instead, it is a painful reminder of age care’s decline across the world. The direct approach to filming pairs strongly with Sandra’s clear-eyed understanding of responsibility. Georg’s ailments, including his blindness and incoherent speech, are irreversible. Consequently, he is filmed in an unflinching manner that influences Sandra’s unwavering care for him. There is levity though because the title suggests hopefulness. Sandra’s anxiety over her father’s care is countered by her desire for Clement’s loyalty. Evidently, the measured but realistic filmic style is delicate about age and evokes Sandra’s understanding of responsibility towards her father.

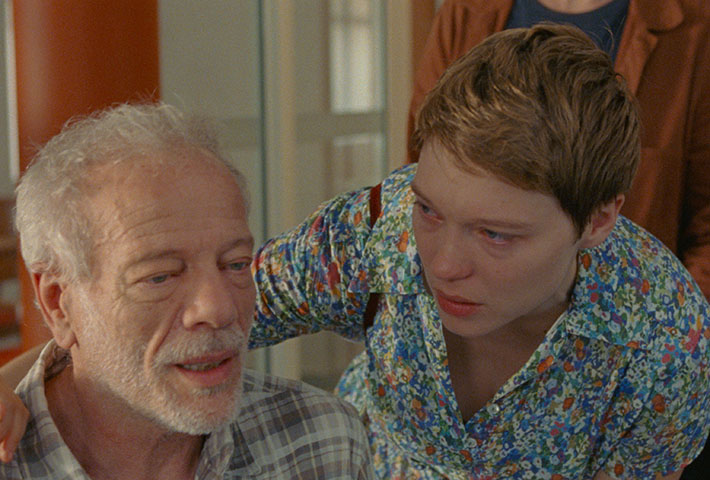

Léa Seydoux has grown into an enormously versatile and accomplished actress. She is thriving in Europe and Hollywood and has rarely been better than what she achieves as Sandra. She is in almost every scene and her emotional performance perfectly dissolves into the same dramatic naturalism issued by Hansen-Løve’s camera. She effortlessly shifts between the raw pain of watching her father disintegrate and being elevated by the love of her daughter and the passion of a new and exciting relationship. There are many moments where we see the toll the conflicts impose on her, such as when tears well in her eyes over her father’s state, when she grows distracted at work, and when she challenges Clement about his decision to keep sleeping with his wife. Pascal Greggory’s performance also impresses due to the utterly the convincing way he captures Georg’s confusion and physical decline. Apparently, the actor even strongly resembles Hansen-Løve’s own father. A particularly poignant moment involving Georg is when Sandra tries playing Schubert to relax him. In another strong scene, she explains to Linn that Georg’s books reflect who he is stronger than the fading man in age care. Melvil Poupaud makes Clement charismatic and shares great chemistry with Seydoux so that we do not resent the nature of the affair but witness the intense passion involved. Even Camille Leban Martins as Linn has an endearing, naturalistic presence on screen. There is an unusual scene where Linn fakes having a limp but is taken to a doctor. Though admittedly odd the moment reinforces Sandra’s unwavering duty to her family.

What makes One Fine Morning affecting and emotional is what Hansen-Løve chooses to subtract. Rather than leaning into condescending or sentimental takes on mortality, the film is upfront about how difficult age care is for patients and their families. The highly direct approach to how these troubling scenes are photographed reflects the director’s refusal to indulge in obvious melodrama and personal conflict. Instead, she builds the subtle duality of the protagonist. The film dramatises Sandra’s loyalty towards her father in knowing he is declining while she wrestles with the uncertainty of a new, secretive relationship. A significant reason why the film and the audience do not judge Sandra’s affair is because she is entrenched in the thematic idea of balancing responsibilities with personal needs. It is a highly European perspective to observe the relationship’s physicality rather than exploring the ethics of the situation as a Western film would have undertaken. It is true the film has too many false endings and could have been shortened. However, nothing detracts from Léa Seydoux who makes Sandra sympathetic and deserving of the glimpses of daylight that drive her forward.

Summary: The understated family drama depicted throughout One Fine Morning is effectively staged and moving to watch.