EMMA BEEBY INTERVIEW – MATA HARI

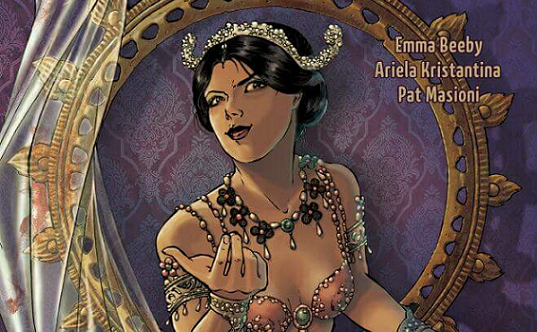

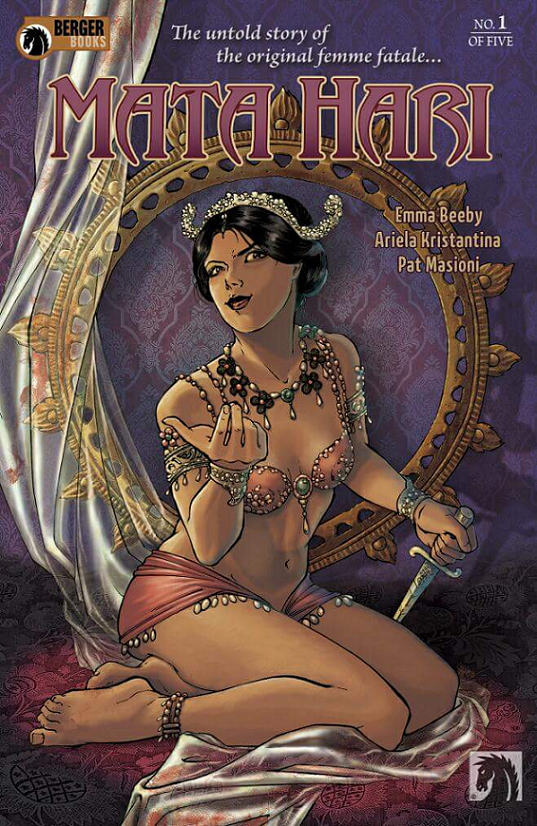

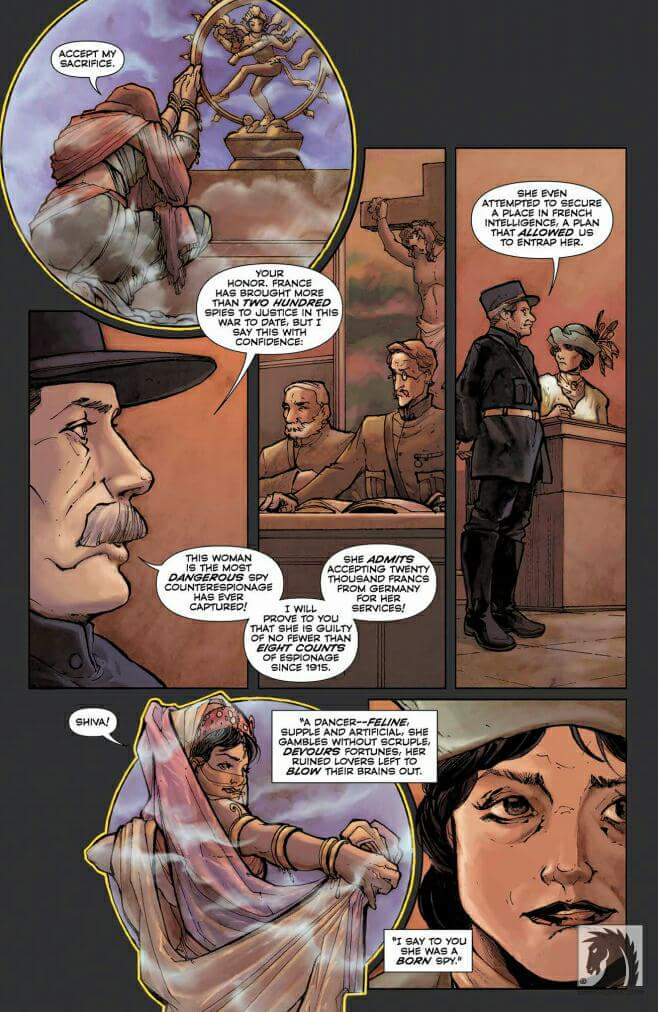

Mata Hari, international sex symbol and double-agent executed by French firing squad in 1917, is a woman who possesses an almost mystical allure for her colourful and audacious life. The myth behind this mysterious woman is explored by writer Emma Beeby and artist Ariela Kristantina, who have used biographies and M15 files to unveil the true story of the woman behind the legend.

Emma Beeby took the time to talk to Impulse Gamer about this legendary femme fatale, the challenges she encountered with translating her story and what it was about Mata Hari that appealed to her personally.

For those who are unfamiliar with Mata Hari, can you give us a quick rundown and who she was, what she did, and why people should pick this comic up and read it?

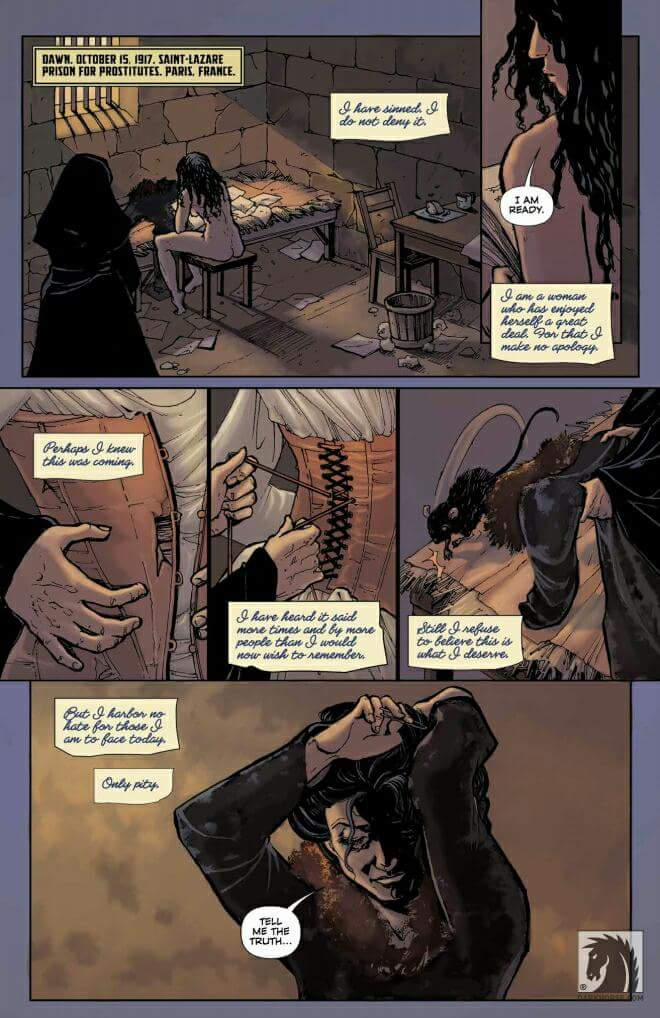

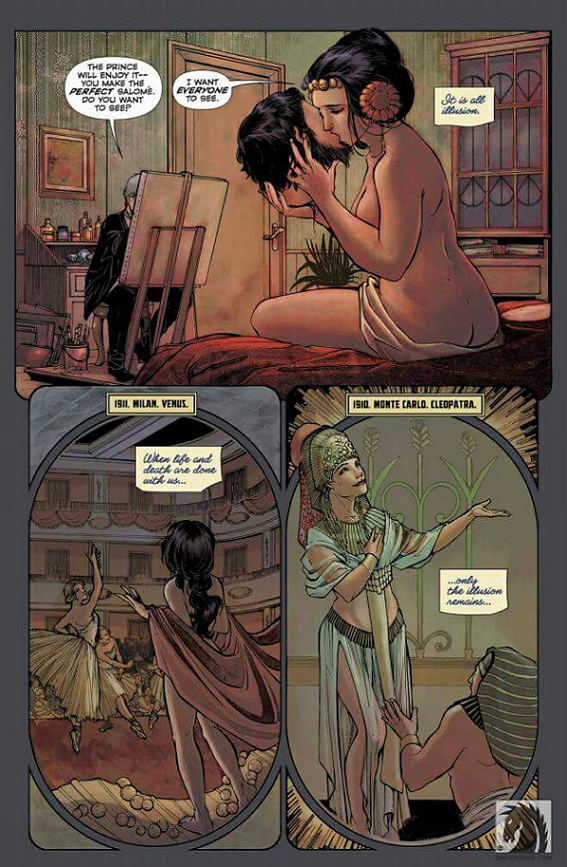

Mata Hari is the stage name of a Dutch woman called Margaretha Zelle who found fame and fortune at the start of the 20th century as one of the first exotic dancers to take off (most) of her clothes, claiming it was a holy dance of ‘The Orient.’ She danced for royalty, for the elite of Europe, taking many lovers who supported her lavish lifestyle. When World War I broke out she became a spy for Germany and then for France, who arrested and executed her as a double agent. All these things are facts about her, but very far from the truth. There’s this myth to unravel, where desperation drove most of the actions in her life. The comic goes behind a lot of this seemingly glamorous and boundary-breaking tale to the less well-known story.

I rather like how you balance and present her personal and private life against her public profile. How did you go about translating these aspects of her life and identity on paper?

That’s really what intrigued me about the story. Mata Hari seemed to understand myth and the effect it would have in creating one about herself, to embody this stage identity completely, as she knew the truth was not something that would help her. But one informed the creation of the other. It was a time when women seldom worked and relied almost completely on men for access to money. She was left penniless, homeless and her daughter taken from her by her ex-husband, even when she won legal custody. He ensured she could get no work, and no credit. She had learned from a young age that the thing men wanted from her seemed to be her body and had briefly turned to prostitution. Her invention of Mata Hari allowed her to show her body to roomfuls of men, but by claiming to be royal and holy, claiming it was in fact art, she would never have to be touched. It was a solution, and it made her rich. So there’s a context to it that completely changes our understanding of what she did. I wanted to show the interplay of that by using the telling of the myth, which is what she writes in her memoir, while we see the reality of her memories on the page.

Did you struggle in capturing the spirit of Mata Hari, or did you find this to be an easy role to step into?

The most difficult thing in truly grasping her spirit is how performative she is. At all times, she is showing the version of herself that she believes will work best with the audience she has, whether one person or a theatre-full. I think she goes into every situation with her head held high and believing she can charm her way out of any problems. I think it really shocked her that she could not charm her way out of her prison and execution. I see her as being driven by both faith in herself and a terror that everything might be suddenly taken away, as it often was.

What were some of the challenges you encountered when translating her story from what we know about her?

I found both too much and too little information in different places! I’ve simplified and made small changes so that the story flows, but have kept to the essential facts. Maybe one of the hardest things was how much is missing in her history about her relationships with the women in her life. Much, much more is written about the rich men she had as lovers, though they only seemed to mean so much to her, so I don’t give them any more weight than I think she does. I am sure there are significant relationships to her we barely know about: an example being that she lived alone with her mother until her mother’s death, so it’s likely she discovered the body, but that is given almost no discussion in the biographical narrative. It’s just assumed that her father leaving was of much more importance. It’s not clear how her mother died, but she was young, and poverty and the shame of recent divorce played a large part, and I even wondered if she committed suicide, something often not disclosed officially at the time.

Margaretha seems to get on well with everyone, winning over everyone from the nuns in prison, the wives and mothers of her lovers, but still, women are largely missing in her story but were not absent, so where I knew she was around women, I have tried to give her relationships with them.

What was it about Mata Hari that appealed to you personally?

She was extraordinary, but I don’t think it’s so much her herself, as it is what her story shows about that time and our time and the lives of women, in the West, and those under colonial rule of the time also. I was interested in my, and others’ reactions to her, my expectations of who she was rather than what the truth, and in the reactions people had at the time to the way she lived, and even now how she can be meaningful and symbolic. Her story made me think and question myself, and I think I wanted to explore that more than anything else.

Mata Hari was known for her blatant displays and reinvention of cultural appropriation. How did you go about handling this aspect of her life, without it becoming offensive?

Well, here’s the thing: she was an actual colonialist. She went with her husband, who was then an officer charged with ‘subduing’ the local population in what is now part of Indonesia to make way for Dutch control. The Dutch actions were horrific, they recruited local men for their armies and used them help wipe out thousands more, and it was brutal and cruel in near every way imaginable. Most of the Dutch barracks had on-site brothels full of local women and girls; officers often had a common-law wife, usually abandoned in favour of a ‘pure blooded’ white woman when they eventually started to come over or handed over to another officer when the officer’s posting ended.

When Margaretha arrived in the then Dutch East Indies, she didn’t look as pale and blonde as the usual Dutch woman, and it was thought by most that she was half-Indonesian, so she and her husband, who was a Major and supposed to be in charge, were shunned. It was the primary cause of strain in her marriage: the whole point of her being there was to help her husband look the part, and she was failing to be white enough. Not that there’s evidence that this made her sympathetic to the women there! She clearly took to the country, she wore traditional Indonesian clothes, learned to speak some Malay, very much frowned upon by the Dutch, but it’s hard to see that as anything other than a starting point in appropriation. It helped seed the idea of Mata Hari, that she could ‘pass’. She learned, or imitated, some of her dance moves by watching the women who looked after her children. Their names were not recorded because the Dutch would call them ‘babu’ meaning ‘carer of’ along the name of the child they looked after. Ariela tells me the word is now considered an ugly slur. So I’m afraid it is offensive, she seemingly didn’t give it a second’s thought when she claimed her new identity. Of course, it was a different time, but I have no desire to excuse it for that, I can only try to show what she did and not give her actions a more generous interpretation than the evidence supports just because it’s her story.

Some people view Mata Hari as being a feminist martyr and a symbol of sexual empowerment. Is this something that you found yourself exploring when telling her story?

She is absolutely seen as these things, but I think both are more symbolic than showing her own attitudes. She wasn’t much of a feminist. She didn’t seem to like suffragettes, she accused some of stealing from her luggage and it reads like that’s exactly the sort of thing she’d expect from them. When she was younger, she seemed to think that as she was ‘beautiful’ that should guarantee her an easy life of money and marriage, as if she’d already succeeded at being a woman. She later wanted financial and personal independence from men, and she achieved that by using her body and looks. It was used against her in court to prove she was an immoral dangerous spy. How much she would have seen her life as a struggle against the whole system of patriarchy, I don’t know.

The sexual empowerment idea is difficult as well, she was abused as a girl and young woman and had gone into prostitution when she saw no other option. She wrote about having a ‘distaste’ for sex because of husband’s treatment of her, and it took her some years to get past that. ‘Mata Hari’ was a sexual fantasy also designed to not be seen as too sexually available. She used lovers to give her a life of luxury, one even gave her a chateau, but how much did she really want to be with these men, or enjoy them personally or sexually? She claimed she loved to take men to bed and ‘think nothing of money’ but can the courtesan say anything else? I have had to think about that as she’s famous for her lovers, and I do think she found some sexual liberation once she was in control of her life and not having to conform to an impossible Victorian standard. In her final years she fell in love with a Russian officer and got engaged, and her reaction to this was to take a series of men to her bed, paying ones, to save enough to have a nest egg to be with the man she loved. So, as an idea of sexual liberation, I’d say it’s complicated.

That she can embody all these ideas and symbols about women, and some that would perhaps surprise her, is one of the interesting things about telling her story.

What was it like working alongside Ariela Kristantina and Pat Masioni?

Ariela is an amazing artist. I’m always blown away by the pages and how much she brings to them, more than I can evoke in a script. She’s given Mata Hari some signature expressions and really brought her to life. I try to provide Ariela with lots of references but she always finds even more than I do – there’s so much reality and history on each page. Ariela is living in Indonesia just now, and for those parts of the series set there it has benefitted so much from her knowledge. It means we are in very different time zones, so mostly we communicate by email, so she can discuss with Karen or me what she’s doing with the pages. It’s not a case of send the script away and wait for finished art. We’re all discussing as we go along.

Pat has had a tough task, most of the reference is black and white, so he’s had to bring all that into colour, and I just marvel at it. There are things that he gives real attention to that could be seen as incidental, like the wallpaper in her hotel room when she’s arrested, but it shows how much grandeur she lived in before prison, and the comic is all the richer for those details.