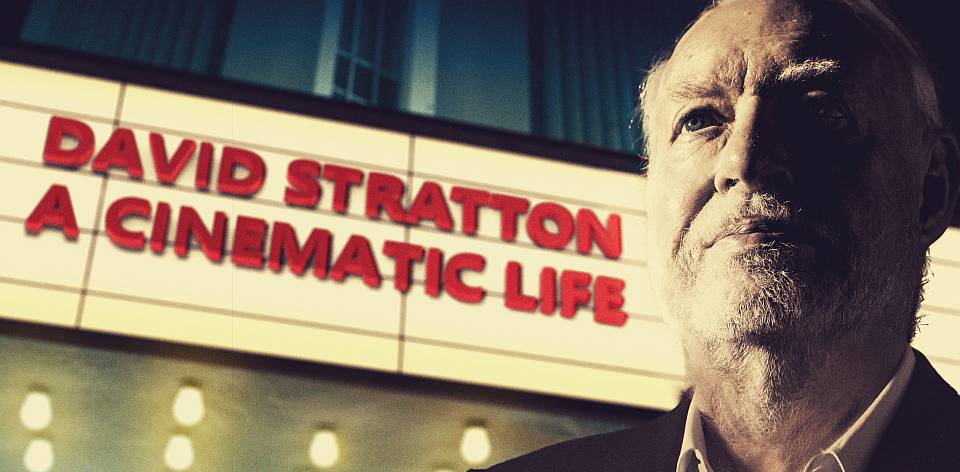

David Stratton: A Cinematic Life – Film Review

Reviewed by Damien Straker on the 28th of February 2017

Transmission presents a film by Sally Aitken

Produced by Jo-anne McGowan

Starring: David Stratton

Rating: PG

Running time: 95 minutes

Release Date: the 9th of March 2017

The title David Stratton: A Cinematic Life stipulates the indecisiveness of this unfocused documentary. It is initially shaped by an interesting structural gimmick or hook, but one that fails to be sustained throughout the entire piece. Directed by Sally Aitken and starring Australian film critic David Stratton, who narrates the film, A Cinematic Life unconvincingly pairs the experiences of David’s migration from England to Australia with classic Australian cinema.

Early on, the juxtaposition is evoked through David’s empathy with various film characters. He compares his experience of being an outsider to the main character in Wake in Fright (1971) and humorously visits the film’s real life pub. He offers similar parallels to Muriel from Muriel’s Wedding (1994) for being the black sheep of the family, arguing that his rejection of his father’s family business, a grocery store, made him feel at one with the story.

However, the structure never deepens beyond these rather tenuous and superfluous links. In some cases, Sally Aitken dispenses with the idea entirely by including films irrelevant to David’s life. Selling A Cinematic Life as a documentation of an individual becomes less honest once it reveals itself to be a clip show of Australia’s greatest cinematic hits with strictly anecdotal commentary and remarks provided by actors and Stratton himself.

The enjoyability of seeing these classic films strikes because of their timelessness, but the analysis is superficial and does not shed new light on these films, particularly for those who have already taken a film course on Australian film history. Some of the same films from the courses provided at the University of Sydney, where David gives his lectures, are used including Indigenous films such as Jedda (1955). The gimmick of tying David’s experiences to these films becomes redundant. Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge (2001) for example is mentioned but with no reference to David’s love of the can-can, nor does Mad Max (1979) by George Miller illuminate David’s hidden life as a rogue motorcycle cop.

The scope of the documentary springs free from Sally Aitken’s hands. Familiar and important film topics are also touched upon but with no depth, including censorship, exploitation cinema and the non-existence of Australia’s film industry in the 1960s. Judicious selection of films belonging to these topics, meaning less films in general, followed by a deeper discussion of David’s connections to them, would have enriched the documentary’s intelligence. Apparently the documentary will air as a longer television mini-series, which could provide more time to each topic.

As an illumination of David himself, the film is as shrouded as his work life. David’s brother, who has no interest in film is interviewed, but as much as Sally Aitken tries tying fictional families to David’s own fallout with his father, we see nothing from his immediate family with his wife and children curiously omitted. Instead, we learn more than we ever wanted to know about the functions of David’s filing cabinet. Moments of genuine emotion are rare. A medium close-up shot of David recalling himself as a child rejecting his father’s gift is the genuine emotional heartbeat the rest of the film would have relished.

Asking for more light on David’s personal life stems from A Cinematic Life having an unfortunately superior companion piece. The documentary Life Itself (2014) is a stirring feature that traces film critic Roger Ebert’s life, including his time in hospital. Under far more awful circumstances than anything seen here, Ebert and his wife Chaz opened themselves to life’s most brutal and intimate moments. Life Itself used the arc of Ebert’s life to encompass topics including criticism itself, whereas this movie falters by splintering David’s life from the films, which makes its objectives misguided.

Luckily, the film is resuscitated by conversations between David and his At the Movies co-star Margaret Pomeranz. The humour and the light barbs in these scenes proves the endurance of their friendship. Yet it’s also a bit like sitting with two friends retelling their best jokes. The fallout of David’s no score rating for Romper Stomper (1992) emerges once again, as does the anger of director Geoffrey Wright who describes David as “a pompous windbag”. This is another example of the film revisiting information common in film circles or for anyone who has already read David’s autobiography “I Peed on Fellini”.

The film could be characterised as an adaptation of the book given the amount of overlapping information. Yet a pivotal omission from the book, particularly in the context of the Australian film industry, is David’s dismissal of the slew of awful Australian comedies from the early 2000s. In terms of modern films, Beautiful Kate (2009) and Animal Kingdom (2010) are mentioned but there’s no discourse around the inconsistency of local films today. Contemporary film criticism also goes unmentioned, barring David’s foray into “Twittering”.

The film’s instinct to abbreviate, compress or omit information is contradicted by its generally sluggish movement. The pacing is lazy and overextends even the meagre running time. The film doesn’t reach cinematic heights of its own either. Most of the form and the content is provided by footage from the classic films, making it unfair to praise this film visually. A television screen would perfectly suffice for watching the film without losing any impact.

A cinematic life is also descriptive of the idolised light shined upon this documentary’s subject. While David is fairly distant in the real world, familiar raves about his film knowledge are paired with footage of him signing autographs for commoners when he has precious few seconds to spare. The idealistic way in which he’s framed would be fine if it weren’t for actress Jacki Weaver’s short-sighted and unpleasant comment about “bozos” on the Internet having too much say when David is king!

In much the same way that Roger Ebert made film criticism hip, Margaret and David incidentally pioneered many a bozo to writing, record and publish film criticism on the Internet. Jacki Weaver’s comment typifies how too much of this documentary looks backwards not forwards. The value of modern criticism today isn’t merely blasting terrible films, but championing smaller movies and providing honest commentary about the state of our local film industry. When the day comes when David Stratton’s filing cabinet is locked for good, the maturity of our own cinematic lives will be called upon. Who answers back must wrestle themselves free of inferiority and self-doubt and remind us that even in the darkness of the cinema we are never alone.

Summary: The title David Stratton: A Cinematic Life stipulates the indecisiveness of this unfocused documentary.